This week I take a look at how yeast ferments wort into beer by looking at a simple graph from White Labs on the fermentation timeline.

Fermentation Over Time

Most of us know the basics of fermentation where yeast consumes simple sugars from the wort, chiefly maltose, and converts them into alcohol, carbon dioxide gas as well as aromatic and flavor compounds.

The detailed process is surprisingly complex – a single cell organism takes in wort sugars including maltose, sucrose, fructose, glucose, maltotriose, along with nitrogen, oxygen and various minerals and converts them in a multistage process involving rapid growth, respiration and fermentation to the 4 major compounds mentioned above. However for today I’m not going to dive into the organic chemistry involved.

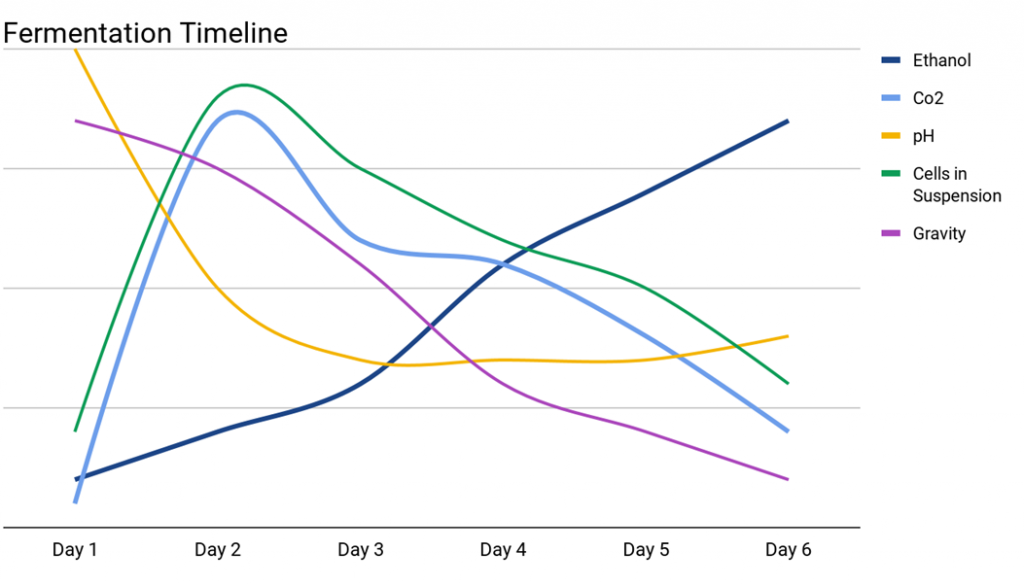

Instead I wanted to focus on the chart above from White Labs which shows the first six days of fermentation. You can click on the image above to enlarge it. Here we see the major cycles and changes going on fairly clearly during the primary stage of fermentation.

First, looking at the cells in suspension (green line), we see that the growth phase of fermentation is very rapid, occupying about 24 hours. Yeast cells typically can expand by a factor of 5-6x in a single cycle, so your yeast packet or starter will rapidly grow during this phase. The yeast also will absorb any oxygen and nutrients you have added at this point to fuel its growth, which is why aeration is important.

Carbon dioxide activity (blue line) also increases rapidly during the growth phase, though it does trail off slightly as fermentation progresses. Typically CO2 activity peaks near the point of peak growth, though CO2 will continue to be produced as long as active fermentation continues.

The gravity of the wort does not drop much during the initial cell growth phase, though it will start to drop more rapidly once peak cell activity is reached. Its not unusual to see a kind of exponential decay beyond that point as the sugars are consumed rapidly past peak cell levels and then gravity decline slows as fewer fermentable sugars are available.

While most home brewers don’t track beer pH, it is important to note that the pH of the wort drops very rapidly even during the growth phase and continues to drop through the peak periods of fermentation. A slight rise in pH is normal as fermentation completes. This can be important if working with sour beers, particularly those made using kettle souring or with acidic fruits. If the pH during fermentation drops to the low 3.0-3.2 range it can actually start to inhibit fermentation. In this case you may actually need to add something like potassium bicarbonate to raise the pH up a bit to allow fermentation to complete.

While this particular graph stops at 6 days, obviously fermentation is not complete at that point. There are important processes going on even as the yeast begins to fall out of suspension that aid in the maturation process. These include items like the remaining yeast cells mopping up the diacetyl in the finished beer. Thats why you need to provide time after your primary fermentation has completed for the yeast to flocculate (fall out) and mature.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s article from the BeerSmith Home Brewing Blog. Please subscribe for regular weekly delivery, and don’t hesitate to leave a comment or send this article to a friend.

Thanks for a fine article. That diagram was very interesting, but one line I’d like to see would be one showing how glycogen stores are used and built up.

Actually I’d love to have an in-depth article about glycogen, and the role it plays in beer fermentation. It seems it – and trehalose, too – plays a crucial role, and that we should try to pitch yeast with good stores of it. And so the question of how we do that, is a vital one.

In the latest edition of How to Brew (p.122) Palmer tells us to take the starter off the stir plate halfway through the propagation, because the yeast needs a period when oxygen is not supplied in order to build up the gycogen stores. I have not seen that advice elsewhere, and I wonder what the basis is. It’s also pretty hard to ascertain when that halway mark is reached. One is left more or less to guessing, and that’s not very satisfying.

That advice may be very sound, though – I’d just like to understand better what it’s based on, and what the consequences of letting the starter spin all the way to completion is.