Most brewers understand that yeast starters are important for making your beer. If you pitch the proper quantity of yeast, your beer will ferment fully and give you a clean finish. Some time back, I wrote an article on how to create a basic yeast starter, but that only touched briefly on the important topic of starter size. This week I dive in with an in-depth overview of yeast starters, how to properly size them and how to best use them.

Using too little yeast (under-pitching) will result in a diaceytl flavor (butterscotch) in your finished beer as well as high finishing gravities. While far less common, over-pitching (too much yeast) can also result in off flavors as the yeast will run out of sugar before it completes a full fermentation cycle.

Using too little yeast (under-pitching) will result in a diaceytl flavor (butterscotch) in your finished beer as well as high finishing gravities. While far less common, over-pitching (too much yeast) can also result in off flavors as the yeast will run out of sugar before it completes a full fermentation cycle.

Recently I had Chris White from White Labs as a guest on the BeerSmith podcast, and read his excellent book Yeast: The Practical Guide to Beer Fermentation (Brewing Elements Series)(Amazon Aff Link). I also did quite a bit of research while developing a yeast starter tool for the next version of BeerSmith. In both cases, I learned a lot about yeast starters and how to properly calculate and size them. I thought I might share this knowledge with you.

The Pitching Rate – How Much Yeast Do I Need?

The amount of yeast you need (called the pitching rate) varies depending on the type of yeast you are using. Most sources quote 1 million yeast cells per milliliter per degree plato for an average beer. A more accurate figure from Dave Miller is 0.75 million/ml-P for ales, 1.5 million/ml-P for lager and 1.0 milion/ml-P for hybrid yeasts. To calculate the number of yeast cells you need overall, you simply multiply the pitching rate by the volume of the beer (in ml) and gravity of the beer (in plato) to get the number of live cells you need to pitch.

So for a sample ale of 5.25 gallons and 1.048 gravity – the number (if you do the math converting to ml and plato) is 177 billion cells. So if you pitch a starter with 177 billion cells, you will have a proper amount of yeast for fermenting the beer.

Liquid and Dry Yeast Pack Size

Knowing how many yeast cells you need for a given batch provides a starting point, but next you need to figure out how to meet that need. Most home brewers use commercial liquid or dry yeast packets to prime their starter.

The two primary liquid yeast providers in the US are White labs and Wyeast. White labs yeast comes in vials that contain from 80-120 billion cells each, with an average of about 100 billion cells for a fresh vial. Wyeast labs come in large and small smack packs. The large pack is comparable to the vials, with about 100 billion cells per smack pack. The small smack pack has considerably less – about 18-20 billion cells per pack.

Since even the 100 billion packs/vials are less than the 177 billion cells we calculated for a moderate ale, this means that most 5 gallon batches would benefit from a starter.

Dry yeast packets (Danstar, DCL SafeAle and others), which are considerably denser, contain about 18 billion yeast cells per gram. Dry yeast packets come in small and large packet sizes of 5 grams and 11.5 grams. Running the numbers, the 5 gram packet contains about 90 billion yeast cells and the 11.5 gram packet contains 207 billion yeast cells.

Viability

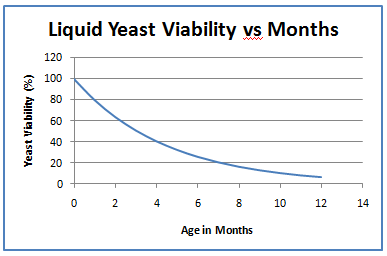

The figures above are for fresh liquid or dry yeast packets. Unfortunately both dry and liquid yeast cells do die off as they are stored, making older yeast less effective. The percentage of live yeast in a sample is called its viability – a brand new packet is 100% viable, but loses viability over time. The effect is much more pronounced for liquid yeast than dry yeast.

Dry yeast has a long shelf life. If stored at room temperature it loses only about 20% of its viability per year (<2% per month), and if refrigerated it only loses 4% per year. So if you refrigerate your dry yeast it will last many years.

Liquid yeast, which must be refrigerated, has a much shorter shelf life. Wyeast lists their shelf life at 5-6 months while White labs recommends 4 months. White labs on their web site says that after 30 days, their vials have 75-85% viability, which is a loss of about 20% of viability in the first month. If we compound this loss (20% per month), this means that the viability of liquid yeast follows this progression:

- 1 month – 80% viable

- 2 months – 64% viable

- 3 months – 51% viable

- 4 months – 41% viable

- 5 months – 33% viable

- 6 months – 26% viable

Now even at 6 months, with 26% viability you can make a suitable starter, but you need to take into account the viability of liquid yeast when calculating the starter size.

Dry Yeast

Dry yeast does not by itself need a starter, as long as you pitch enough packets of yeast. Generally all that is needed is that you hydrate the yeast with warm water for about 20 minutes before pitching. Use lukewarm water at 105F (41C) in the amount of 10 ml per gram of yeast. This works out to 50 ml (1.7 oz) of water per 5 gram packet or 115 ml (3.9 oz) per large dry packet.

If you are using dry yeast as the seed for a starter to step up for a larger starter, hydrate it as usual and then add the yeast to the starter. As above, the 5 gram packet contains about 90 billion yeast cells and the 11.5 gram packet contains 207 billion yeast cells. Age is seldom a significant factor unless the yeast is over a year old or has not been stored properly.

Liquid Yeast

Liquid yeast, due to both the cell count and viability lost as it ages, often does require a starter. To figure out how large the starter needs to be, you first want to calculate the number of packets needed. Generally the way to start is by calculating how many viable yeast cells you have in your vials or packets. This is done by multiplying the starting yeast cells for a packet by the viability (use the table above). So if you have a White labs vial that was manufactured 2 months ago, you will have 100 billion x 64% which is 64 billion cells per vial.

Next calculate the growth in cells needed. The beer in the earlier example (5.25 gallons of ale wort at 1.048) requires 177 billion cells. If we were to use 1 vial of 2 month old ale yeast at 64 billion cells, we would calculate the growth at 177 billion divided by 64 billion = 2.77 — meaning that we need to expand the yeast 2.77 times to get to our target population.

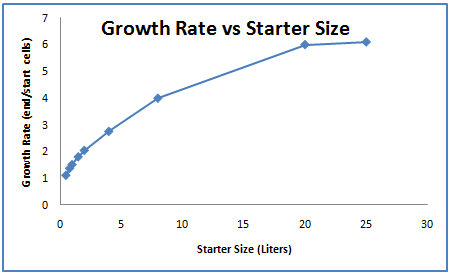

This means our starter needs to grow 2.77 times, from about 64 billion cells to about 177 billion cells in order to create the proper pitching rate for our finished beer. The next step is to figure out how large a starter we need to create to achieve this growth. One might think this is a straightforward calculation, but it turns out that the growth of yeast is not linear – it depends on how many yeast cells you have to start with.

This means our starter needs to grow 2.77 times, from about 64 billion cells to about 177 billion cells in order to create the proper pitching rate for our finished beer. The next step is to figure out how large a starter we need to create to achieve this growth. One might think this is a straightforward calculation, but it turns out that the growth of yeast is not linear – it depends on how many yeast cells you have to start with.

The graph to the right, extracted from a table in Chris White’s yeast book, shows the growth rate from an experiment with a 100 billion cell vial of yeast added to starters of varying size. Obviously if you start with a very small starter, and a lot of yeast there is not much sugar to support growth and the growth rate remains low. At the other end of the spectrum, if you pitch a relatively small amount of yeast into a large starter (approaching 20 liters) you get high growth.

However, growth rate peaks out at around 6.0, so pitching 100 billion cells is not going to get you much more than 600 billion cells total (6x growth rate), no matter how large the starter is.

Starter Size Coming in Part 2

This week I covered how to calculate the number of yeast cells for a given batch as well as the viability of liquid and dry yeasts. I also explained how to calculate the number of dry yeast packs needed and how to hydrate those. We started to look at growth rates for liquid yeast starters, a topic which I’ll continue in part two. I’ll also take a closer look at the above graph and how it helps us calculating the actual starter size for a liquid yeast sample in part two.

Thank you for joining me on the BeerSmith Home Brewing Blog. Hopefully you have subscribed to receive more articles and also are listening to the new BeerSmith podcast. Also I wanted to thank you very much for your support this year and wish you a very happy holiday season as we close out 2010.

Brad,

Very interesting…I normally get my yeast from a local brewery. I’m guessing it is in the range of 1/2 a quart, would this be too much, or how could I determine the amount to use?

Jay

Jay – I did not cover the sizing for reusing yeast slurry, but I will include it in part 2. With slurry it is important that you use it quickly as the viability degrades within days and weeks rather than months.

Great start to the series. Looking forward to learning a bunch more as you continue!

Jim,

Thanks for the kind comments! I think you will enjoy part 2!

Brad

Great write up Brad – can’t wait for part II.

I hate to think how many times I’ve brewed/fermented and used single yeast packets or smack packs this year without doing a starter. The beer usually turns out, but could always be… better. This will be a great help as I look to hone my skills a bit.

Thanks Mike,

I’m taking a few days off for the holidays but should have part 2 out shortly!

Brad

Thanks for the article it was very well explained, as a beginner I had no idea how important yeast is.

Thanks! – Yeast is as important as any of the other ingredients and some people say even more so, as it ultimately adds about 500 different flavor compounds to the beer!

Pingback: yeast starter size - Home Brew Forums

Brad,

I have had great success with yeast starters but feel that it has been partly due to some fortunate guesstimates.

I can’t find a Package date on any of the White Labs yeast vials that I’ve used, only a “Best Before” date.

Is there a rule of thumb for inputting a packaged date into the BeerSmith2 yeast starter tool by backing up from the “Best By” date? I would really like to be more precise on this.

Terry

As usual, very interesting article. Thank you.

What about culturing from liquid yeast vials or packs? Is there a loss in viability when culturing? Besides a starter (I’m assuming a malt at 1.040), and probably some yeast nutrients, what else is in a vial or smack – pack of liquid yeast?

Pingback: Storing Your Beer Brewing Hops, Grains and Yeast | Home Brewing Beer Blog by BeerSmith